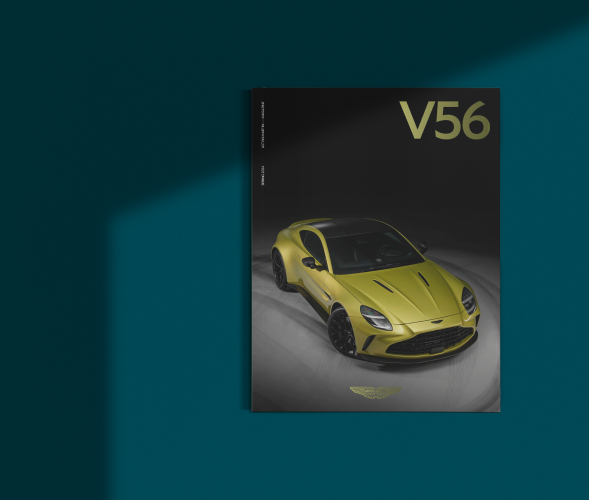

Driving

Heaven

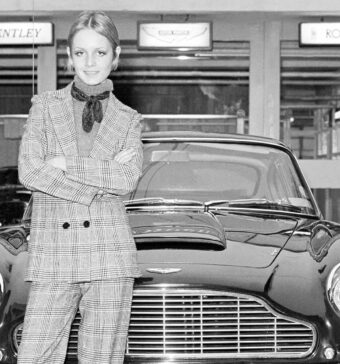

Valhalla takes the world by storm in dynamic fashion

My Aston Martin

Dopamine Hit

Doctor to elite athletes and passionate car collector Vernon Cooley shares how his love of rarity and high-performance fuels his growing Aston Martin collection, led by his prized Valour

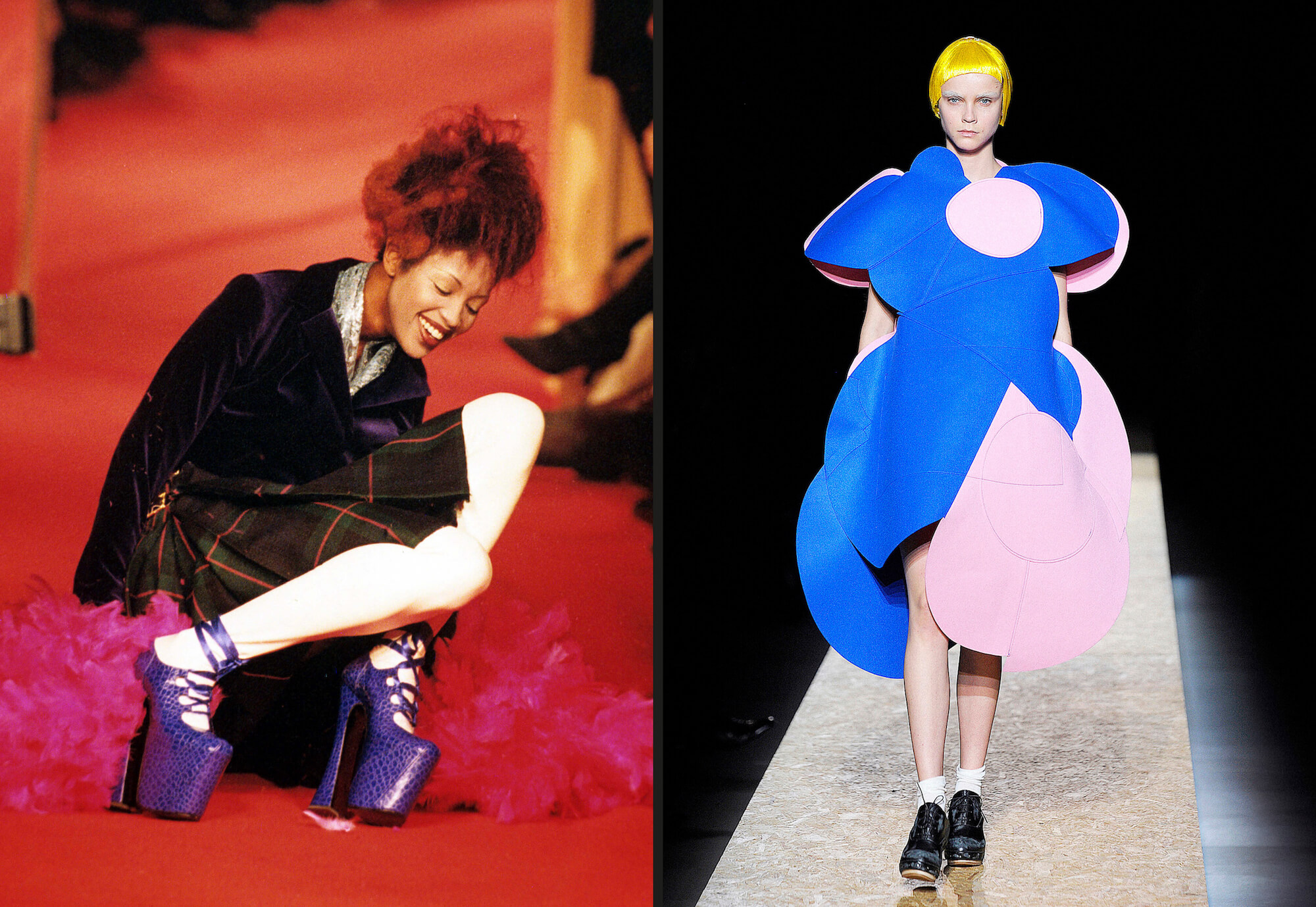

SONIC

THRILLS

Crystal KeiKei journeys through Snowdonia in the DBX707, with Bowers & Wilkins delivering the soundtrack

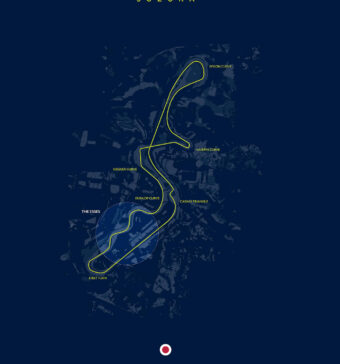

ROAD TO

LE MANS

In 1959, Aston Martin triumphed at the 24 Hours of Le Mans with a historic one-two finish. James Taylor retraces the team's journey to the race in the road-going Aston Martin Valkyrie, as its racing siblings prepare to race around the clock once more

Want to read more?Kickstart your journey with a Premium Subscription to the Aston Martin magazine. Receive the official printed edition, delivered directly to your door three times a year throughout 2024, and unlock even more content online. Subscribe now to embark on a year of automotive adventures from the world of Aston Martin and beyond.Log inSubscribe

Want to read more?Kickstart your journey with a Premium Subscription to the Aston Martin magazine. Receive the official printed edition, delivered directly to your door three times a year throughout 2024, and unlock even more content online. Subscribe now to embark on a year of automotive adventures from the world of Aston Martin and beyond.Log inSubscribe