He has led more laps than anyone on the current Formula 1 grid bar Lewis Hamilton, Max Verstappen and Fernando Alonso, yet you might not have heard of him. His name is Bernd Mayländer and he is F1’s safety car driver.

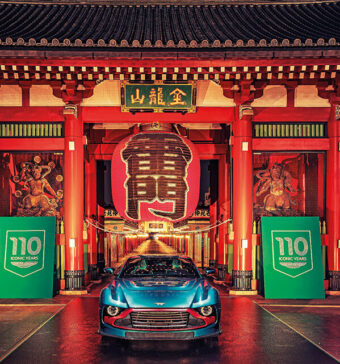

At every grand prix, you’ll find Bernd near the pitlane exit sitting in his car (which is currently either a Mercedes-AMG GT Black Series or an Aston Martin Vantage F1 Edition, the marques alternating from one GP weekend to the next), strapped in with his helmet on and the engine running. He’ll be monitoring the session or race via his on-board TV and listening for any radio instructions. Is he praying for a crash, I ask him, so he can go out and drive?

Before we get to that, let’s find out what he does and how he got here. Whenever there is a big accident or the track is obstructed in some way, Mayländer appears in an eight-cylinder tyre-squealing chorus to lead the field of F1 cars safely around the circuit and past the danger zone. He has undertaken this important duty since 2000. Some races, he doesn’t need to get involved. At others, he ends up leading the lion’s share of the laps. He led 46 per cent of the rain-affected Canadian GP in 2011, the longest race in history. Winner Jenson Button only led for one and a half laps.

Mayländer Jr’s first F1 race, as a spectator, was the 1977 German Grand Prix at Hockenheim. Niki Lauda won, he recalls. He started karting in 1984, and went on to race in Formula Ford, the Porsche Carrera Cup, and the DTM and the FIA GT Championship with Mercedes-Benz. In 2000, he won the Nürburgring 24 Hours in a Porsche 911 GT3-R. Mayländer talks wistfully about going there a decade earlier when he was 18 and buying a ticket so he could take to the track and destroy his tyres.

Among Mayländer’s other achievements is a world record for driving 100,000 miles in a single month. He and a handful of others did it in a stock Mercedes E320 Diesel saloon, lapping an oval in Texas that was littered with snakes at an average speed of 140mph, 24 hours-a-day for 30 days. “The snakes would slither up to the top of the banking at sunset, to get the last of the day’s heat. That was fine, the problem was when these huge birds arrived and started pecking at them.”

Among Mayländer’s other achievements is a world record for driving 100,000 miles in a single month. He and a handful of others did it in a stock Mercedes E320 Diesel saloon, lapping an oval in Texas that was littered with snakes at an average speed of 140mph, 24 hours-a-day for 30 days. “The snakes would slither up to the top of the banking at sunset, to get the last of the day’s heat. That was fine, the problem was when these huge birds arrived and started pecking at them.”

On Thursday afternoons, Bernd and medical car driver Bruno Correia are given one hour to drive as fast as they can. They need to know where the limit is. Sometimes they swap cars – this year’s medical car will be the new Aston Martin DBX707. Bernd always makes a note of the lap times to compare with his efforts the previous year. However, when leading a race, Mayländer is less about the stopwatch. First and foremost, the safety car must never crash. “A couple of times I’ve been close, with aquaplaning in the wet. I’ve sometimes been glad of the traction control and ABS. It’s important to remember we’re not in the competition, I can’t win anything.

“The pressure is always the same, but the circumstances are different. Circuits change, weather can be unpredictable and no two accidents are the same. But pressure is there, and pressure is good because you need to focus. There’s no room for mistakes. The safety cars are a lot more drivable than they were 20 years ago, I can tell you that.” He describes the turn-of-the-century CL55 AMG as a limousine. The Aston Martin Vantage, he says, suits tracks like Singapore and Baku especially well. “It’s a little softer than the GT, there’s more movement, and that’s really helpful when you’re driving on the limit. It gives more feedback.”

Alongside him sits Richard Darker, an FIA technical assistant. “Richard is like my co-pilot in an aeroplane cockpit. He’s the spotter and he mans the radio communications. We’re told by Race Control: “Safety car standby.” We switch on our flashing lights. Then we wait for the order to deploy”. Which leads me back to my original question: Does he hope for a crash? “The races where you don’t see me are the best races,” he replies.

What do Bernd’s family and friends think of his career? “They call me Mr Safety Car. I’m not sure I like that, because I’m still a racer at heart. I still feel like I’m 35. I don’t feel any older than Alonso, anyway. I think we are both still quick enough.”